Cleveland Tool And Design Cleveland Georgia

City and county seat of Cuyahoga County, Ohio, United States

City in Ohio, United States

| Cleveland | |

|---|---|

| City | |

| City of Cleveland | |

Clockwise, from top: Downtown Cleveland skyline; the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame; Fountain of Eternal Life statue; the West Side Market; West Pierhead Lighthouse; FirstEnergy Stadium; the James A. Garfield Memorial; East 4th Street; south entrance to the Cleveland Museum of Art; and one of the eight Guardians of Traffic | |

| Flag Seal | |

| Nicknames: The Forest City | |

| Motto(s): Progress & Prosperity | |

| |

Interactive maps of Cleveland | |

| Coordinates: 41°28′56″N 81°40′11″W / 41.48222°N 81.66972°W / 41.48222; -81.66972 Coordinates: 41°28′56″N 81°40′11″W / 41.48222°N 81.66972°W / 41.48222; -81.66972 | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Ohio |

| County | Cuyahoga |

| Founded | July 22, 1796; 225 years ago (1796-07-22) |

| Incorporated (village) | December 23, 1814; 206 years ago (1814-12-23) |

| Incorporated (city) | March 6, 1836; 185 years ago (1836-03-06) [1] |

| Named for | Moses Cleaveland |

| Government | |

| • Type | Strong mayor / Council |

| • Body | Cleveland City Council |

| • Mayor | Frank G. Jackson (D) |

| Area [2] | |

| • City | 82.48 sq mi (213.62 km2) |

| • Land | 77.73 sq mi (201.33 km2) |

| • Water | 4.75 sq mi (12.29 km2) |

| • Urban | 772 sq mi (1,999.4 km2) |

| • Metro | 3,979 sq mi (10,307 km2) |

| • CSA | 11,624.49 sq mi (30,107.4 km2) |

| Elevation [3] | 653 ft (199 m) |

| Population (2020[4]) | |

| • City | 372,624 |

| • Rank | 54th |

| • Density | 4,901.51/sq mi (1,892.49/km2) |

| • Urban | 1,780,673 (US: 25th) |

| • Metro | 2,057,009 (US: 33rd) |

| • CSA | 3,599,264 (US: 17th) |

| Demonym(s) | Clevelander |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| ZIP Codes | ZIP Codes[5]

|

| Area code | 216 |

| FIPS code | 39-16000 |

| GNIS feature ID | 1066654[3] |

| Major airports | Cleveland Hopkins International Airport, Cleveland Burke Lakefront Airport |

| Interstates | |

| Rapid Transit | |

| Website | clevelandohio.gov |

Cleveland ( KLEEV-lənd), officially the City of Cleveland, is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio, and the county seat of Cuyahoga County.[6] It is located along the southern shore of Lake Erie, across the U.S. maritime border with Canada and approximately 60 miles (100 kilometers) west of the Ohio-Pennsylvania state border.

The largest city on Lake Erie and one of the most populous urban areas in the country,[7] Cleveland anchors the Greater Cleveland Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA) and the Cleveland–Akron–Canton Combined Statistical Area (CSA). The CSA is the most populous combined statistical area in Ohio and the 18th largest in the United States, with a population of 3,633,962 in 2020.[8] [9] The city proper, with a 2020 population of 372,624, ranks as the 54th-largest city in the U.S.,[4] as a larger portion of the metropolitan population lives outside the central city. The seven-county metropolitan Cleveland economy, which includes Akron, is the largest in the state.

Cleveland was founded in 1796 near the mouth of the Cuyahoga River by General Moses Cleaveland, after whom the city was named. It grew into a major manufacturing center due to its location on both the river and the lake shore, as well as numerous canals and railroad lines. A port city, Cleveland is connected to the Atlantic Ocean via the Saint Lawrence Seaway. The city's economy relies on diversified sectors such as manufacturing, financial services, healthcare, biomedicals, and higher education.[10] The gross domestic product (GDP) for the Greater Cleveland MSA was $135 billion in 2019.[11] Combined with the Akron MSA, the seven-county Cleveland–Akron metropolitan economy was $175 billion in 2019, the largest in Ohio, accounting for 25% of the state's GDP.[11]

Designated as a "Gamma -" global city by the Globalization and World Cities Research Network,[12] the city's major cultural institutions include the Cleveland Museum of Art, the Cleveland Museum of Natural History, the Cleveland Orchestra, Playhouse Square, and the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Known as "The Forest City" among many other nicknames, Cleveland serves as the center of the Cleveland Metroparks nature reserve system.[13] The city's major league professional sports teams include the Cleveland Browns, the Cleveland Cavaliers, and the Cleveland Guardians.

History [edit]

Establishment [edit]

Cleveland was established on July 22, 1796, by surveyors of the Connecticut Land Company when they laid out Connecticut's Western Reserve into townships and a capital city. They named the new settlement "Cleaveland" after their leader, General Moses Cleaveland.[14] Cleaveland oversaw the New England-style design of the plan for what would become the modern downtown area, centered on Public Square, before returning home, never again to visit Ohio.[14] The first permanent European settler in Cleaveland was Lorenzo Carter, who built a cabin on the banks of the Cuyahoga River.[15]

The settlement served as an important supply post for the U.S. during the Battle of Lake Erie in the War of 1812.[16] Locals adopted Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry as a civic hero and erected a monument in his honor decades later.[17] The Village of Cleaveland was incorporated on December 23, 1814.[18] In spite of the nearby swampy lowlands and harsh winters, the town's waterfront location proved to be an advantage, giving it access to Great Lakes trade. It grew rapidly after the 1832 completion of the Ohio and Erie Canal. This key link between the Ohio River and the Great Lakes connected it to the Atlantic Ocean via the Erie Canal and Hudson River, and later via the Saint Lawrence Seaway. Its products could reach markets on the Gulf of Mexico via the Mississippi River. The town's growth continued with added railroad links.[19]

In 1831, the spelling of the town's name was altered by The Cleveland Advertiser newspaper. In order to fit the name on the newspaper's masthead, the editors dropped the first "a", reducing the city's name to Cleveland, which eventually became the official spelling.[20] In 1836, Cleveland, then only on the eastern banks of the Cuyahoga River, was officially incorporated as a city.[18] That same year, it nearly erupted into open warfare with neighboring Ohio City over a bridge connecting the two communities.[21] Ohio City remained an independent municipality until its annexation by Cleveland in 1854.[18]

Home to a vocal group of abolitionists,[22] [23] Cleveland (code-named "Station Hope") was a major stop on the Underground Railroad for escaped African American slaves en route to Canada.[24] The city also served as an important center for the Union during the American Civil War.[25] [26] Decades later, in July 1894, the wartime contributions of those serving the Union from Cleveland and Cuyahoga County would be honored with the opening of the city's Soldiers' and Sailors' Monument on Public Square.[27]

Growth and expansion [edit]

After the war, the city witnessed rapid growth. Its prime geographic location as a transportation hub between the East Coast and the Midwest played an important role in its development as a commercial center. In 1874, the First Woman's National Temperance Convention was held in Cleveland, and adopted the formation of the Woman's Christian Temperance Union.[28] Cleveland served as a destination for iron ore shipped from Minnesota, along with coal transported by rail. In 1870, John D. Rockefeller founded Standard Oil in Cleveland. In 1885, he moved its headquarters to New York City, which had become a center of finance and business.[29]

By the early 20th century, Cleveland had emerged as a major American manufacturing center. Its businesses included automotive companies such as Peerless, People's, Jordan, Chandler, and Winton, maker of the first car driven across the U.S. Other manufacturers in Cleveland produced steam-powered cars, which included those by White and Gaeth, and electric cars produced by Baker.[30] The city's industrial growth was accompanied by significant strikes and labor unrest, as workers demanded better working conditions. In 1881–86, 70-80% of strikes were successful in improving labor conditions in Cleveland.[31]

Known as the "Sixth City" due to its position as the sixth largest U.S. city at the time,[32] [33] Cleveland counted major Progressive Era politicians among its leaders, most prominently the populist Mayor Tom L. Johnson, who was responsible for the development of the Cleveland Mall Plan.[34] The era of the City Beautiful movement in Cleveland architecture, this period also saw wealthy patrons support the establishment of the city's major cultural institutions. The most prominent among them were the Cleveland Museum of Art, which opened in 1916, and the Cleveland Orchestra, established in 1918.[35] [36]

Cleveland's economic growth and industrial jobs attracted large waves of immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe as well as Ireland.[37] African American migrants from the rural South also arrived in Cleveland (among other Northeastern and Midwestern cities) as part of the Great Migration for jobs, constitutional rights, and relief from racial discrimination.[38] Between 1910 and 1930, the African American population of Cleveland grew by more than 400%.[39] By 1920, the year in which the Cleveland Indians won their first World Series championship, Cleveland had grown into a densely-populated metropolis of 796,841 with a foreign-born population of 30%, making it the fifth largest city in the nation.[40] [41] At this time, Cleveland saw the rise of radical labor movements in response to the conditions of the largely immigrant and migrant workers. In 1919, the city attracted national attention amid the First Red Scare for the Cleveland May Day Riots, in which socialist demonstrators clashed with anti-socialists.[42] [43]

Despite the immigration restrictions of 1921 and 1924, the city's population continued to grow throughout the 1920s. Prohibition first took effect in Ohio in May 1919 (although it was not well-enforced in Cleveland), became law with the Volstead Act in 1920, and was eventually repealed nationally by Congress in 1933.[44] The ban on alcohol led to the rise of speakeasies throughout the city and organized crime gangs, such as the Mayfield Road Mob, who smuggled bootleg liquor across Lake Erie from Canada into Cleveland.[44] [45] The Roaring Twenties also saw the establishment of Cleveland's Playhouse Square and the rise of the risqué Short Vincent entertainment district.[46] [47] [48] The Bal-Masque balls of the avant-garde Kokoon Arts Club scandalized the city.[49] [50] Jazz came to prominence in Cleveland during this period.[51] [52] [53]

In 1929, the city hosted the first of many National Air Races, and Amelia Earhart flew to the city from Santa Monica, California in the Women's Air Derby (nicknamed the "Powder Puff Derby" by Will Rogers).[54] The Van Sweringen brothers commenced construction of the Terminal Tower skyscraper in 1926 and, by the time it was dedicated in 1930, Cleveland had a population of over 900,000.[55] [40] The era of the flapper also marked the beginning of the golden age in Downtown Cleveland retail, centered on major department stores Higbee's, Bailey's, the May Company, Taylor's, Halle's, and Sterling Lindner Davis, which collectively represented one of the largest and most fashionable shopping districts in the country, often compared to New York's Fifth Avenue.[56]

Cleveland was hit hard by the Wall Street Crash of 1929 and the subsequent Great Depression. A center of union activity, the city saw significant labor struggles in this period, including strikes by workers against Fisher Body in 1936 and against Republic Steel in 1937.[31] The city was also aided by major federal works projects sponsored by President Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal.[57] In commemoration of the centennial of Cleveland's incorporation as a city, the Great Lakes Exposition debuted in June 1936 at the city's North Coast Harbor, along the Lake Erie shore north of downtown.[58] Conceived by Cleveland's business leaders as a way to revitalize the city during the Depression, it drew four million visitors in its first season, and seven million by the end of its second and final season in September 1937.[59]

On December 7, 1941, Imperial Japan attacked Pearl Harbor and declared war on the United States. One of the victims of the attack was a Cleveland native, Rear Admiral Isaac C. Kidd.[60] The attack signaled America's entry into World War II. A major hub of the "Arsenal of Democracy", Cleveland under Mayor Frank Lausche contributed massively to the U.S. war effort as the fifth largest manufacturing center in the nation.[60] During his tenure, Lausche also oversaw the establishment of the Cleveland Transit System, the predecessor to the Greater Cleveland Regional Transit Authority.[61]

Late 20th and early 21st centuries [edit]

After the war, Cleveland initially experienced an economic boom, and businesses declared the city to be the "best location in the nation".[62] [63] In 1949, the city was named an All-America City for the first time and, in 1950, its population reached 914,808.[64] [40] In sports, the Indians won the 1948 World Series, the hockey team, the Barons, became champions of the American Hockey League, and the Browns dominated professional football in the 1950s. As a result, along with track and boxing champions produced, Cleveland was declared the "City of Champions" in sports at this time.[65] The 1950s also saw the rising popularity of a new music genre that local WJW (AM) disc jockey Alan Freed dubbed "rock and roll".[66]

However, by the 1960s, Cleveland's economy began to slow down, and residents increasingly sought new housing in the suburbs, reflecting the national trends of suburban growth following federally subsidized highways.[67] Industrial restructuring, particularly in the railroad and steel industries, resulted in the loss of numerous jobs in Cleveland and the region, and the city suffered economically. The burning of the Cuyahoga River in June 1969 brought national attention to the issue of industrial pollution in Cleveland and served as a catalyst for the American environmental movement.[68]

Housing discrimination and redlining against African Americans led to racial unrest in Cleveland and numerous other Northern U.S. cities.[69] [70] In Cleveland, the Hough riots erupted from July 18 to 23, 1966, and the Glenville Shootout took place from July 23 to 25, 1968.[38] In November 1967, Cleveland became the first major American city to elect an African American mayor, Carl B. Stokes, who served from 1968 to 1971 and played an instrumental role in restoring the Cuyahoga River.[71] [72]

In December 1978, during the turbulent tenure of Dennis Kucinich as mayor, Cleveland became the first major American city since the Great Depression to enter into a financial default on federal loans.[73] By the beginning of the 1980s, several factors, including changes in international free trade policies, inflation, and the savings and loan crisis, contributed to the recession that severely affected cities like Cleveland.[74] While unemployment during the period peaked in 1983, Cleveland's rate of 13.8% was higher than the national average due to the closure of several steel production centers.[75] [76] [77]

The city began a gradual economic recovery under Mayor George V. Voinovich in the 1980s. The downtown area saw the construction of the Key Tower and 200 Public Square skyscrapers, as well as the development of the Gateway Sports and Entertainment Complex—consisting of Progressive Field and Rocket Mortgage FieldHouse—and the North Coast Harbor, including the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, FirstEnergy Stadium, and the Great Lakes Science Center.[78] The city emerged from default in 1987.[18]

Skyline of Cleveland in 2012.

By the turn of the 21st century, Cleveland succeeded in developing a more diversified economy and gained a national reputation as a center for healthcare and the arts. Additionally, it has become a national leader in environmental protection, with its successful cleanup of the Cuyahoga River.[79] The city's downtown has experienced dramatic economic and population growth since 2010,[80] but the overall population has continued to decline.[81] Challenges remain for the city, with economic development of neighborhoods, improvement of city schools, and continued encouragement of new immigration to Cleveland being top municipal priorities.[82] [83]

Geography [edit]

NASA satellite photograph of Cleveland at night

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 82.47 square miles (213.60 km2), of which 77.70 square miles (201.24 km2) is land and 4.77 square miles (12.35 km2) is water.[84] The shore of Lake Erie is 569 feet (173 m) above sea level; however, the city lies on a series of irregular bluffs lying roughly parallel to the lake. In Cleveland these bluffs are cut principally by the Cuyahoga River, Big Creek, and Euclid Creek.

The land rises quickly from the lake shore elevation of 569 feet. Public Square, less than one mile (1.6 km) inland, sits at an elevation of 650 feet (198 m), and Hopkins Airport, 5 miles (8 km) inland from the lake, is at an elevation of 791 feet (241 m).[85]

Cleveland borders several inner-ring and streetcar suburbs. To the west, it borders Lakewood, Rocky River, and Fairview Park, and to the east, it borders Shaker Heights, Cleveland Heights, South Euclid, and East Cleveland. To the southwest, it borders Linndale, Brooklyn, Parma, and Brook Park. To the south, the city also borders Newburgh Heights, Cuyahoga Heights, and Brooklyn Heights and to the southeast, it borders Warrensville Heights, Maple Heights, and Garfield Heights. To the northeast, along the shore of Lake Erie, Cleveland borders Bratenahl and Euclid.

Cityscapes [edit]

Architecture [edit]

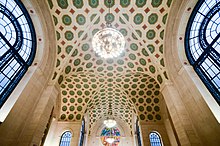

Cleveland's downtown architecture is diverse. Many of the city's government and civic buildings, including City Hall, the Cuyahoga County Courthouse, the Cleveland Public Library, and Public Auditorium, are clustered around the open Cleveland Mall and share a common neoclassical architecture. They were built in the early 20th century as the result of the 1903 Group Plan. They constitute one of the most complete examples of City Beautiful design in the United States.[86] [87]

Completed in 1927 and dedicated in 1930 as part of the Cleveland Union Terminal complex, the Terminal Tower was the tallest building in North America outside New York City until 1964 and the tallest in the city until 1991.[55] It is a prototypical Beaux-Arts skyscraper. The two newer skyscrapers on Public Square, Key Tower (currently the tallest building in Ohio) and the 200 Public Square, combine elements of Art Deco architecture with postmodern designs. Cleveland's architectural treasures also include the Cleveland Trust Company Building, completed in 1907 and renovated in 2015 as a downtown Heinen's supermarket,[88] and the Cleveland Arcade (sometimes called the Old Arcade), a five-story arcade built in 1890 and renovated in 2001 as a Hyatt Regency Hotel.[89] [90]

Running east from Public Square through University Circle is Euclid Avenue, which was known for its prestige and elegance as a residential street. In the late 1880s, writer Bayard Taylor described it as "the most beautiful street in the world".[91] Known as "Millionaires' Row", Euclid Avenue was world-renowned as the home of such major figures as John D. Rockefeller, Mark Hanna, and John Hay.[92] [93] [94]

Cleveland's landmark ecclesiastical architecture includes the historic Old Stone Church in downtown Cleveland and the onion domed St. Theodosius Russian Orthodox Cathedral in Tremont,[95] [96] [97] along with myriad ethnically inspired Roman Catholic churches.[98]

Parks and nature [edit]

Downtown Cleveland from Edgewater Park

Known locally as the "Emerald Necklace", the Olmsted-inspired Cleveland Metroparks encircle Cleveland and Cuyahoga County. The city proper is home to the Metroparks' Brookside and Lakefront Reservations, as well as significant parts of the Rocky River, Washington, and Euclid Creek Reservations. The Lakefront Reservation, which provides public access to Lake Erie, consists of four parks: Edgewater Park, Whiskey Island–Wendy Park, East 55th Street Marina, and Gordon Park.[99] Three more parks fall under the jurisdiction of the Euclid Creek Reservation: Euclid Beach, Villa Angela, and Wildwood Marina.[100] Bike and hiking trails in the Brecksville and Bedford Reservations, along with Garfield Park further north, provide access to trails in the Cuyahoga Valley National Park. The extensive system of trails within Cuyahoga Valley National Park extends south into Summit County, offering access to Summit Metro Parks as well. Also included in the system is the renowned Cleveland Metroparks Zoo, established in 1882. Located in Big Creek Valley, the zoo has one of the largest collections of primates in North America.[101]

The Cleveland Metroparks provides ample opportunity for outdoor recreational activities. Hiking and biking trails, including single-track mountain bike trails, wind extensively throughout the parks.[102] Rock climbing is available at Whipp's Ledges at the Hinckley Reservation.[103] During the summer months, kayakers, paddle boarders, and rowing and sailing crews can be seen on the Cuyahoga River and Lake Erie. In the winter months, downhill skiing, snowboarding, and tubing are available not far from downtown at the Boston Mills/Brandywine and Alpine Valley ski resorts.

In addition to the Metroparks, the Cleveland Public Parks District oversees the city's neighborhood parks, the largest of which is the historic Rockefeller Park. The latter is notable for its late 19th century landmark bridges, the Rockefeller Park Greenhouse, and the Cleveland Cultural Gardens, which celebrate the city's ethnic diversity.[104] [105] Just outside of Rockefeller Park, the Cleveland Botanical Garden in University Circle, established in 1930, is the oldest civic garden center in the nation.[106] In addition, the Greater Cleveland Aquarium, located in the historic FirstEnergy Powerhouse in the Flats, is the only independent, free-standing aquarium in the state of Ohio.[107]

Neighborhoods [edit]

The Cleveland City Planning Commission has officially designated 34 neighborhoods in Cleveland.[108] Centered on Public Square, Downtown Cleveland is the city's central business district, encompassing a wide range of subdistricts, such as the Nine-Twelve District, the Campus District, the Civic Center, and Playhouse Square. It also historically included the lively Short Vincent entertainment district, which emerged in the 1920s, reached its height in the 1940s and 1950s, and disappeared with the expansion of National City Bank in the late 1970s.[47] [48] Mixed-use areas, such as the Warehouse District and the Superior Arts District, are occupied by industrial and office buildings as well as restaurants, cafes, and bars.[109] The number of downtown condominiums, lofts, and apartments has been on the increase since 2000 and especially 2010, reflecting the neighborhood's dramatic population growth.[80] Recent downtown developments also include the Euclid Corridor Project and the revival of East 4th Street.[110]

Map of the territorial evolution of Cleveland

Clevelanders geographically define themselves in terms of whether they live on the east or west side of the Cuyahoga River.[111] The East Side includes the neighborhoods of Buckeye–Shaker, Buckeye–Woodhill, Central, Collinwood (including Nottingham), Euclid–Green, Fairfax, Glenville, Goodrich–Kirtland Park (including Asiatown), Hough, Kinsman, Lee–Miles (including Lee–Harvard and Lee–Seville), Mount Pleasant, St. Clair–Superior, Union–Miles Park, and University Circle (including Little Italy). The West Side includes the neighborhoods of Brooklyn Centre, Clark–Fulton, Cudell, Detroit–Shoreway, Edgewater, Ohio City, Old Brooklyn, Stockyards, Tremont (including Duck Island), West Boulevard, and the four neighborhoods colloquially known as West Park: Kamm's Corners, Jefferson, Bellaire–Puritas, and Hopkins. The Cuyahoga Valley neighborhood (including the Flats) is situated between the East and West Sides, while the Broadway–Slavic Village neighborhood is sometimes referred to as the South Side.

Several neighborhoods have begun to attract the return of the middle class that left the city for the suburbs in the 1960s and 1970s. These neighborhoods are on both the West Side (Ohio City, Tremont, Detroit–Shoreway, and Edgewater) and the East Side (Collinwood, Hough, Fairfax, and Little Italy). Much of the growth has been spurred on by attracting creative class members, which in turn is spurring new residential development.[112] A live-work zoning overlay for the city's near East Side has facilitated the transformation of old industrial buildings into loft spaces for artists.[113]

Climate [edit]

| Cleveland | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Typical of the Great Lakes region, Cleveland exhibits a continental climate with four distinct seasons, which lies in the humid continental (Köppen Dfa)[114] zone. Summers are hot and humid while winters are cold and snowy. The Lake Erie shoreline is very close to due east–west from the mouth of the Cuyahoga west to Sandusky, but at the mouth of the Cuyahoga it turns sharply northeast. This feature is the principal contributor to the lake-effect snow that is typical in Cleveland (especially on the city's East Side) from mid-November until the surface of Lake Erie freezes, usually in late January or early February. The lake effect also causes a relative differential in geographical snowfall totals across the city: while Hopkins Airport, on the city's far West Side, has only reached 100 inches (254 cm) of snowfall in a season three times since record-keeping for snow began in 1893,[115] seasonal totals approaching or exceeding 100 inches (254 cm) are not uncommon as the city ascends into the Heights on the east, where the region known as the 'Snow Belt' begins. Extending from the city's East Side and its suburbs, the Snow Belt reaches up the Lake Erie shore as far as Buffalo.[116]

The all-time record high in Cleveland of 104 °F (40 °C) was established on June 25, 1988,[117] and the all-time record low of −20 °F (−29 °C) was set on January 19, 1994.[118] On average, July is the warmest month with a mean temperature of 74.5 °F (23.6 °C), and January, with a mean temperature of 29.1 °F (−1.6 °C), is the coldest. Normal yearly precipitation based on the 30-year average from 1991 to 2020 is 41.03 inches (1,042 mm).[119] The least precipitation occurs on the western side and directly along the lake, and the most occurs in the eastern suburbs. Parts of Geauga County to the east receive over 44 inches (1,100 mm) of liquid precipitation annually.[120]

| Climate data for Cleveland (Cleveland Airport), 1991–2020 normals,[a] extremes 1871–present[b] | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 73 (23) | 77 (25) | 83 (28) | 88 (31) | 93 (34) | 104 (40) | 103 (39) | 102 (39) | 101 (38) | 93 (34) | 82 (28) | 77 (25) | 104 (40) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 58.9 (14.9) | 60.8 (16.0) | 70.8 (21.6) | 80.3 (26.8) | 86.7 (30.4) | 91.8 (33.2) | 92.7 (33.7) | 91.3 (32.9) | 88.8 (31.6) | 80.5 (26.9) | 68.9 (20.5) | 60.0 (15.6) | 93.9 (34.4) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 35.8 (2.1) | 38.5 (3.6) | 47.1 (8.4) | 60.1 (15.6) | 71.1 (21.7) | 79.8 (26.6) | 83.7 (28.7) | 82.0 (27.8) | 75.6 (24.2) | 63.7 (17.6) | 51.3 (10.7) | 40.4 (4.7) | 60.8 (16.0) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 29.1 (−1.6) | 31.1 (−0.5) | 38.9 (3.8) | 50.4 (10.2) | 61.2 (16.2) | 70.4 (21.3) | 74.5 (23.6) | 73.0 (22.8) | 66.4 (19.1) | 55.1 (12.8) | 44.0 (6.7) | 34.3 (1.3) | 52.4 (11.3) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 22.3 (−5.4) | 23.7 (−4.6) | 30.7 (−0.7) | 40.8 (4.9) | 51.4 (10.8) | 61.1 (16.2) | 65.3 (18.5) | 63.9 (17.7) | 57.1 (13.9) | 46.5 (8.1) | 36.7 (2.6) | 28.2 (−2.1) | 44.0 (6.7) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 1.3 (−17.1) | 4.0 (−15.6) | 12.2 (−11.0) | 25.9 (−3.4) | 36.2 (2.3) | 45.9 (7.7) | 53.3 (11.8) | 51.6 (10.9) | 43.0 (6.1) | 32.1 (0.1) | 20.8 (−6.2) | 9.8 (−12.3) | −2.2 (−19.0) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −20 (−29) | −17 (−27) | −5 (−21) | 10 (−12) | 25 (−4) | 31 (−1) | 41 (5) | 38 (3) | 32 (0) | 19 (−7) | 0 (−18) | −15 (−26) | −20 (−29) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 2.99 (76) | 2.49 (63) | 3.06 (78) | 3.75 (95) | 3.79 (96) | 3.83 (97) | 3.67 (93) | 3.56 (90) | 3.93 (100) | 3.60 (91) | 3.37 (86) | 2.99 (76) | 41.03 (1,042) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 18.4 (47) | 15.1 (38) | 10.8 (27) | 2.7 (6.9) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.1 (0.25) | 4.5 (11) | 12.2 (31) | 63.8 (162) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 17.7 | 14.6 | 14.6 | 14.8 | 13.4 | 11.5 | 10.7 | 10.3 | 10.1 | 12.1 | 13.1 | 15.6 | 158.5 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.01 in) | 13.5 | 10.5 | 7.2 | 2.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 3.8 | 8.4 | 45.8 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 73.3 | 73.0 | 70.4 | 66.1 | 67.3 | 69.0 | 69.8 | 73.1 | 73.7 | 70.8 | 71.9 | 74.1 | 71.0 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 101.0 | 122.3 | 167.0 | 216.0 | 263.6 | 294.6 | 307.2 | 262.2 | 219.0 | 169.5 | 89.8 | 67.8 | 2,280 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 34 | 41 | 45 | 54 | 59 | 65 | 67 | 61 | 59 | 49 | 30 | 24 | 51 |

| Average ultraviolet index | 2 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 7 | 9 | 9 | 8 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 5 |

| Source 1: NOAA (relative humidity and sun 1961–1990)[121] [122] [123] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Weather Atlas[124] (sunshine data) | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Cleveland | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average sea temperature °F (°C) | 34.0 (1.1) | 33.2 (0.6) | 33.5 (0.8) | 40.6 (4.8) | 50.5 (10.3) | 66.5 (19.2) | 76.2 (24.5) | 76.3 (24.6) | 71.2 (21.8) | 62.0 (16.7) | 50.5 (10.3) | 39.3 (4.1) | 52.8 (11.6) |

| Mean daily daylight hours | 10.0 | 11.0 | 12.0 | 13.0 | 15.0 | 15.0 | 15.0 | 14.0 | 12.0 | 11.0 | 10.0 | 9.0 | 12.3 |

| Source: Weather Atlas[124] | |||||||||||||

Demographics [edit]

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1820 | 606 | — |

| 1830 | 1,075 | +77.4% |

| 1840 | 6,071 | +464.7% |

| 1850 | 17,034 | +180.6% |

| 1860 | 43,417 | +154.9% |

| 1870 | 92,829 | +113.8% |

| 1880 | 160,146 | +72.5% |

| 1890 | 261,353 | +63.2% |

| 1900 | 381,768 | +46.1% |

| 1910 | 560,663 | +46.9% |

| 1920 | 796,841 | +42.1% |

| 1930 | 900,429 | +13.0% |

| 1940 | 878,336 | −2.5% |

| 1950 | 914,808 | +4.2% |

| 1960 | 876,050 | −4.2% |

| 1970 | 750,903 | −14.3% |

| 1980 | 573,822 | −23.6% |

| 1990 | 505,616 | −11.9% |

| 2000 | 478,403 | −5.4% |

| 2010 | 396,815 | −17.1% |

| 2020 | 372,624 | −6.1% |

| Source: United States Census records and Population Estimates Program data.[40] [125] [4] | ||

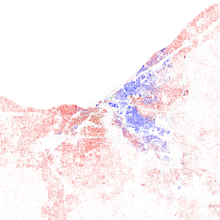

Map of racial distribution in Greater Cleveland, 2010 U.S. Census. Each dot is 25 people:

White

Black

Hispanic

Asian

Other

At the 2020 census, there were 372,624 people and 170,549 households in the city. The population density was 4,901.51 inhabitants per square mile (1,892.5/km2).[4]

The median income for a household in the city was $30,907. The per capita income for the city was $21,223. 32.7% of the population living below the poverty line. Of the city's population over the age of 25, 17.5% held a bachelor's degree or higher, and 80.8% had a high school diploma or equivalent.[4]

According to the 2010 census, 29.7% of Cleveland households had children under the age of 18 living with them, 22.4% were married couples living together, 25.3% had a female householder with no husband present, 6.0% had a male householder with no wife present, and 46.4% were non-families. 39.5% of all households were made up of individuals, and 10.7% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.29 and the average family size was 3.11.[128]

In 2010, the median age in the city was 35.7 years. 24.6% of residents were under the age of 18; 11% were between the ages of 18 and 24; 26.1% were from 25 to 44; 26.3% were from 45 to 64; and 12% were 65 years of age or older. The gender makeup of the city was 48.0% male and 52.0% female.[126]

Ethnicity [edit]

Originally built in 1905 as the Jewish Temple B'nai Jeshurun, this building on Cleveland's East Side, today known as the Shiloh Baptist Church, now serves the African American community.

According to the 2020 census, the racial composition of the city was 40.0% white, 48.8% African American, 0.5% Native American, 2.6% Asian, and 4.4% from two or more races. Hispanics or Latinos of any race were 11.9% of the population.[4]

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, Cleveland saw a massive influx of immigrants from Ireland, Italy, and the Austro-Hungarian, German, Russian, and Ottoman empires, most of whom were attracted by manufacturing jobs.[37] As a result, Cleveland and Cuyahoga County today have substantial communities of Irish (especially in Kamm's Corners and other areas of West Park), Italians (especially in Little Italy and around Mayfield Road), Germans, and several Central-Eastern European ethnicities, including Czechs, Hungarians, Lithuanians, Poles, Romanians, Russians, Rusyns, Slovaks, Ukrainians, and ex-Yugoslav groups, such as Slovenes, Croats, and Serbs.[37] The presence of Hungarians within Cleveland proper was, at one time, so great that the city boasted the highest concentration of Hungarians in the world outside of Budapest.[129] Cleveland has a long-established Jewish community, historically centered on the East Side neighborhoods of Glenville and Kinsman, but now mostly concentrated in East Side suburbs such as Cleveland Heights and Beachwood, home to the Maltz Museum of Jewish Heritage.[130]

The availability of jobs also attracted African Americans from the South. Between 1920 and 1970, the black population of Cleveland, largely concentrated on the city's East Side, increased significantly as a result of the First and Second Great Migrations.[38] Cleveland's Latino community consists primarily of Puerto Ricans, who make up over 80% of the city's Hispanic/Latino population, as well as smaller numbers of immigrants from Mexico, Cuba, the Dominican Republic, South and Central America, and Spain.[131] The city's Asian community, centered on historical Asiatown, consists of Chinese, Koreans, Vietnamese, and other groups.[132] Additionally, the city and the county have significant communities of Albanians,[133] Arabs (especially Lebanese, Syrians, and Palestinians),[134] Armenians,[135] French,[136] Greeks,[137] Iranians,[138] Scots,[37] Turks,[139] and West Indians.[37] A 2020 analysis found Cleveland to be the most ethnically and racially diverse city in Ohio.[140]

Many ethnic festivals are held in Cleveland throughout the year, such as the annual Feast of the Assumption in Little Italy, Russian Maslenitsa in Rockefeller Park, the Cleveland Puerto Rican Parade and Festival in Clark–Fulton, the Cleveland Asian Festival in Asiatown, the Greek Festival in Tremont, and the Romanian Festival in West Park. Vendors at the West Side Market in Ohio City offer many ethnic foods for sale. Cleveland also hosts annual Polish Dyngus Day and Slovene Kurentovanje celebrations.[141] [142] The city's annual Saint Patrick's Day parade brings hundreds of thousands to the streets of Downtown.[143] The Cleveland Thyagaraja Festival held annually each spring at Cleveland State University is the largest Indian classical music and dance festival in the world outside of India.[144] Since 1946, the city has annually marked One World Day in the Cleveland Cultural Gardens in Rockefeller Park, celebrating all of its ethnic communities.[105]

Religion [edit]

The influx of immigrants in the 19th and early 20th centuries drastically transformed Cleveland's religious landscape. From a homogeneous settlement of New England Protestants, it evolved into a city with a diverse religious composition. The predominant faith among Clevelanders today is Christianity (Catholic, Protestant, and Eastern and Oriental Orthodox), with Jewish, Muslim, Hindu, and Buddhist minorities.[145]

Language [edit]

As of 2020[update], 85.3% of Cleveland residents age 5 and older spoke English at home as a primary language.[4] 14.7% spoke a foreign language, including Spanish, Arabic, Chinese, Albanian, and various Slavic languages (Russian, Polish, Serbo-Croatian, and Slovene).[4]

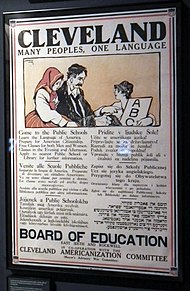

Immigration [edit]

In 1920, Cleveland proper boasted a foreign-born population of 30% and, in 1870, that percentage was 42%.[41] Although the foreign-born population of Cleveland today is not as big as it once was, the sense of identity remains strong among the city's various ethnic communities, as reflected in the Cleveland Cultural Gardens. Within Cleveland, the neighborhoods with the highest foreign-born populations are Asiatown/Goodrich–Kirtland Park (32.7%), Clark–Fulton (26.7%), West Boulevard (18.5%), Brooklyn Centre (17.3%), Downtown (17.2%), University Circle (15.9%, with 20% in Little Italy), and Jefferson (14.3%).[146] Recent waves of immigration have brought new groups to Cleveland, including Ethiopians and South Asians,[147] as well as immigrants from Russia and the former USSR,[148] [149] Southeast Europe (especially Albania),[133] the Middle East, East Asia, and Latin America.[37] In the 2010s, the immigrant population of Cleveland and Cuyahoga County began to see significant growth, becoming one of the fastest growing centers for immigration in the Great Lakes region.[83] A 2019 study found Cleveland to be the city with the shortest average processing time in the nation for immigrants to become U.S. citizens.[150] The city's annual One World Day in Rockefeller Park includes a naturalization ceremony of new immigrants.[105]

Economy [edit]

Cleveland's location on the Cuyahoga River and Lake Erie has been key to its growth. The Ohio and Erie Canal coupled with rail links helped the city become an important business center. Steel and many other manufactured goods emerged as leading industries. The city has since diversified its economy in addition to its manufacturing sector.[10] [151] [31]

Established in 1914, the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland is one of 12 U.S. Federal Reserve Banks.[152] Its downtown building, located on East 6th Street and Superior Avenue, was completed in 1923 by the Cleveland architectural firm Walker and Weeks.[153] The headquarters of the Federal Reserve System's Fourth District, the bank employs 1,000 people and maintains branch offices in Cincinnati and Pittsburgh.[152] The chief executive officer and president is Loretta Mester.[154]

The city is also home to the corporate headquarters of many large companies such as Aleris, American Greetings, Applied Industrial Technologies, Mettler Toledo, Cleveland-Cliffs, Inc., Parker Hannifin, Eaton, Forest City Enterprises, Heinen's Fine Foods, Hyster-Yale Materials Handling, KeyCorp, Lincoln Electric, Medical Mutual of Ohio, Moen Incorporated, NACCO Industries, Nordson, OM Group, Parker-Hannifin, PolyOne, Progressive, RPM International, Sherwin-Williams Company, Steris, Swagelok, Things Remembered, Third Federal S&L, TransDigm Group, Travel Centers of America and Vitamix. NASA maintains a facility in Cleveland, the Glenn Research Center. Jones Day, one of the largest law firms in the U.S., was founded in Cleveland.[155]

The Cleveland Clinic is the largest private employer in the city of Cleveland and the state of Ohio, with a workforce of over 50,000 as of 2019[update].[156] It carries the distinction as being among America's best hospitals with top ratings published in U.S. News & World Report.[157] Cleveland's healthcare sector also includes University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center, MetroHealth medical center, and the insurance company Medical Mutual of Ohio. Cleveland is also noted in the fields of biotechnology and fuel cell research, led by Case Western Reserve University, the Cleveland Clinic, and University Hospitals of Cleveland. The city is among the top recipients of investment for biotech start-ups and research.[158]

Technology is another growing sector in Cleveland. In 2005, the city appointed a "tech czar" to recruit technology companies to the downtown office market, offering connections to the high-speed fiber networks that run underneath downtown streets in several "high-tech offices" focused on Euclid Avenue.[159] Cleveland State University hired a technology transfer officer to cultivate technology transfers from CSU research to marketable ideas and companies in the Cleveland area. Local observers have noted that the city is transitioning from a manufacturing-based economy to a health-tech-based economy.[160]

Education [edit]

Primary and secondary education [edit]

The Cleveland Metropolitan School District is the second-largest K–12 district in the state of Ohio. It is the only district in Ohio under the direct control of the mayor, who appoints a school board.[161] Approximately 1 square mile (2.6 km2) of Cleveland, adjacent the Shaker Square neighborhood, is part of the Shaker Heights City School District. The area, which has been a part of the Shaker school district since the 1920s, permits these Cleveland residents to pay the same school taxes as the Shaker residents, as well as vote in the Shaker school board elections.[162]

Private and parochial schools within Cleveland proper include Benedictine High School, Birchwood School, Cleveland Central Catholic High School, Eleanor Gerson School, Montessori High School at University Circle, St. Ignatius High School, St. Joseph Academy, Villa Angela-St. Joseph High School, Urban Community School, St. Martin de Porres, and The Bridge Avenue School.[163]

Higher education [edit]

Cleveland is home to a number of colleges and universities. Most prominent among them is Case Western Reserve University (CWRU), a widely recognized research and teaching institution in University Circle. A private university with several prominent graduate programs, CWRU was ranked 40th in the nation in 2020 by U.S. News & World Report.[164] University Circle also contains the Cleveland Institute of Art and the Cleveland Institute of Music. Cleveland State University (CSU), based in Downtown Cleveland, is the city's public four-year university. In addition to CSU, downtown hosts the metropolitan campus of Cuyahoga Community College, the county's two-year higher education institution. Ohio Technical College is also based in Cleveland.[165] Cleveland's suburban universities and colleges include Baldwin Wallace University in Berea, John Carroll University in University Heights, Ursuline College in Pepper Pike, and Notre Dame College in South Euclid.[166]

Public library system [edit]

Established in 1869, the Cleveland Public Library is one of the largest public libraries in the nation with a collection of 10,559,651 materials in 2018.[167] Its John G. White Special Collection includes the largest chess library in the world as well as a significant collection of folklore and rare books on the Middle East and Eurasia.[168] [169] [170] Under head librarian William Howard Brett, the library adopted an "open shelf" philosophy, which allowed patrons open access to the library's bookstacks.[171] [172] Brett's successor, Linda Eastman, became the first woman ever to lead a major library system in the world.[173] She oversaw the construction of the library's main building on Superior Avenue, designed by Walker and Weeks and opened on May 6, 1925.[171] David Lloyd George, British Prime Minister from 1916 to 1922, laid the cornerstone for the building.[174] The Louis Stokes Wing addition was completed in April 1997.[171] Between 1904 and 1920, 15 libraries built with funds from Andrew Carnegie were opened in the city.[175] Known as the "People's University," the library presently maintains 27 branches.[167] It serves as the headquarters for the CLEVNET library consortium, which includes over 40 public library systems in the Greater Cleveland Metropolitan Area and Northeast Ohio.[176]

Culture [edit]

Performing arts [edit]

Cleveland is home to Playhouse Square, the second largest performing arts center in the United States behind New York City's Lincoln Center.[177] Playhouse Square includes the State, Palace, Allen, Hanna, and Ohio theaters within what is known as the Cleveland Theater District.[178] The center hosts Broadway musicals, special concerts, speaking engagements, and other events throughout the year. Its resident performing arts companies include Cleveland Ballet, the Cleveland International Film Festival, the Cleveland Play House, Cleveland State University Department of Theatre and Dance, DANCECleveland, the Great Lakes Theater Festival, and the Tri-C Jazz Fest.[179] A city with strong traditions in theater and vaudeville, Cleveland has produced many renowned performers, most prominently comedian Bob Hope.[180]

Outside Playhouse Square, Cleveland is home to Karamu House, the oldest African American theater in the nation, established in 1915.[181] On the West Side, the Gordon Square Arts District in Detroit–Shoreway is the location of the Capitol Theatre, the Near West Theatre, and an Off-Off-Broadway Playhouse, the Cleveland Public Theatre.[182] Cleveland's streetcar suburbs of Cleveland Heights and Lakewood are home to the Dobama Theatre and the Beck Center for the Arts respectively.[183]

Cleveland is home to the Cleveland Orchestra, widely considered one of the world's finest orchestras, and often referred to as the finest in the nation.[184] It is one of the "Big Five" major orchestras in the United States.[185] The Cleveland Orchestra plays at Severance Hall in University Circle during the winter and at Blossom Music Center in Cuyahoga Falls during the summer.[186] The city is also home to the Cleveland Pops Orchestra, the Cleveland Youth Orchestra, the Contemporary Youth Orchestra, the Cleveland Youth Wind Symphony, and the biennial Cleveland International Piano Competition which has, in the past, often featured The Cleveland Orchestra.

One Playhouse Square, now the headquarters for Cleveland's public broadcasters, was initially used as the broadcast studios of WJW (AM), where disc jockey Alan Freed first popularized the term "rock and roll".[66] Cleveland gained a strong reputation in rock music in the 1960s and 1970s as a key breakout market for nationally promoted acts and performers.[187] Its popularity in the city was so great that Billy Bass, the program director at the WMMS radio station, referred to Cleveland as "The Rock and Roll Capital of the World."[187] The Cleveland Agora Theatre and Ballroom has served as a major venue for rock concerts in the city since the 1960s.[188] From 1974 through 1980, the city hosted the World Series of Rock at Cleveland Municipal Stadium.[189]

Jazz and R&B have a long history in Cleveland. Many major figures in jazz, including Louis Armstrong, Cab Calloway, Duke Ellington, Ella Fitzgerald, Dizzy Gillespie, Benny Goodman, Billie Holiday, and Don Redman performed in the city, and legendary pianist Art Tatum regularly played in Cleveland clubs during the 1930s.[52] [53] Gypsy jazz guitarist Django Reinhardt gave his U.S. debut performance in Cleveland in 1946.[190] Prominent jazz artist Noble Sissle was a graduate of Cleveland Central High School, Artie Shaw worked and performed in Cleveland early in his career, and bandleader Phil Spitalny led his first orchestra in Cleveland. The Tri-C Jazz Fest has been held annually in Cleveland at Playhouse Square since 1979, and the Cleveland Jazz Orchestra was established in 1984.[52] [53] Joe Siebert's documentary film The Sax Man on the life of Cleveland street saxophonist Maurice Reedus Jr. was released in 2014.[191]

There is a significant hip hop music scene in Cleveland. In 1997, the Cleveland hip hop group Bone Thugs-n-Harmony won a Grammy for their song "Tha Crossroads".[192]

The city also has a history of polka music being popular both past and present, even having a subgenre called Cleveland-style polka named after the city, and is home to the Polka Hall of Fame. This is due in part to the success of Frankie Yankovic, a Cleveland native who was considered America's Polka King. The square at the intersection of Waterloo Road and East 152nd Street in Cleveland ( 41°34′08″N 81°34′31″W / 41.569°N 81.5752°W / 41.569; -81.5752 ), not far from where Yankovic grew up, was named in his honor.[193]

Film and television [edit]

Cleveland has served as the setting for many major studio and independent films, and, early in American film history, it was even a center for film production. The first film shot in Cleveland was in 1897 by the Edison Company.[194] Before Hollywood became the center for American cinema, filmmaker Samuel R. Brodsky and playwright Robert H. McLaughlin operated a studio at the Andrews mansion on Euclid Avenue (now the WEWS-TV studio).[195] There they produced major silent-era features, such as Dangerous Toys (1921), which are now considered lost.[194] Brodsky also directed the weekly Plain Dealer Screen Magazine that ran in theaters in Cleveland and Ohio from 1917 to 1924.[194]

In the "talkie" era, Cleveland featured in numerous classic Hollywood movies, such as Howard Hawks's Ceiling Zero (1936) with James Cagney and Pat O'Brien, and Hobart Henley's romantic comedy The Big Pond (1930) with Maurice Chevalier and Claudette Colbert, which introduced the hit song "You Brought a New Kind of Love to Me".[194] Michael Curtiz's 1933 pre-Code classic Goodbye Again with Warren William and Joan Blondell was set in Cleveland. Players from the 1948 Cleveland Indians, winners of the World Series, appeared in The Kid from Cleveland (1949). Cleveland Municipal Stadium features prominently in both that film and The Fortune Cookie (1966). Written and directed by Billy Wilder, the latter marked Walter Matthau and Jack Lemmon's first on-screen collaboration and features gameday footage of the 1965 Browns.[194]

Cleveland Fire Department (1900) by the Edison Company, one of the very first films made in Cleveland

Other films set in Cleveland include Jules Dassin's Up Tight! (1968) and Norman Jewison's F.I.S.T. (1978), the latter featuring Sylvester Stallone as a local union leader. Paul Simon chose Cleveland as the opening for his only venture into filmmaking, One-Trick Pony (1980). Clevelander Jim Jarmusch's Stranger Than Paradise (1984)—a deadpan comedy about two New Yorkers who travel to Florida by way of Cleveland—was a favorite of the Cannes Film Festival, winning the Caméra d'Or.[194] Both Major League (1989) and Major League II (1994) reflected the actual perennial struggles of the Cleveland Indians during the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s.[194] Several key scenes from Cameron Crowe's Almost Famous (2000) are set in Cleveland, and both Antwone Fisher (2002) and The Soloist (2009) recount the real-life stories of Cleveland natives. Brothers Joe and Anthony Russo—native Clevelanders—filmed their comedy Welcome to Collinwood (2002) entirely on location in the city. American Splendor (2003)—the biopic of Harvey Pekar, author of the autobiographical comic of the same name—was also filmed in Cleveland. Kill the Irishman (2011) depicts the 1970s turf war in Cleveland between Irish mobster Danny Greene and the Cleveland crime family, while Draft Day (2014) features Kevin Costner as general manager for the Browns.[194] [196]

Cleveland has also doubled for other locations in films. The wedding and reception scenes in The Deer Hunter (1978), while set in the small Pittsburgh suburb of Clairton, were shot in Cleveland's Tremont; U.S. Steel also permitted the production to film in one of its Cleveland mills. Francis Ford Coppola produced The Escape Artist (1982), much of which was shot in Downtown Cleveland. A Christmas Story (1983) was set in Indiana, but drew many of its external shots—including the Parker family home—from Cleveland. The opening shots of Air Force One (1997) were filmed in and above Severance Hall. Downtown Cleveland also doubled for New York in Spider-Man 3 (2007) and the climax of The Avengers (2012). More recently, Captain America: The Winter Soldier (2014), The Fate of the Furious (2017), and Judas and the Black Messiah (2021) were all filmed in the city. Future Cleveland productions are handled by the Greater Cleveland Film Commission.[194] [196] [197]

In television, the city is the setting for the popular network sitcom The Drew Carey Show, starring Cleveland native Drew Carey.[198] Hot in Cleveland, a comedy that aired on TV Land, premiered on June 16, 2010, and ran for six seasons until its finale on June 3, 2015.[199] [200] Later episodes of the reality show Keeping Up With the Kardashians have been partially filmed in Cleveland, after series star Khloe Kardashian began a relationship with Cleveland Cavaliers center Tristan Thompson.[201] Cleveland Hustles, the CNBC reality show co-created by LeBron James, was filmed in the city.[182]

Literature [edit]

Langston Hughes, preeminent poet of the Harlem Renaissance and child of an itinerant couple, lived in Cleveland as a teenager and attended Central High School in Cleveland in the 1910s.[202] At Central High, Hughes was taught by Helen Maria Chesnutt, daughter of renowned Cleveland-born African American novelist Charles W. Chesnutt.[203] He also wrote for the school newspaper and started writing his earlier plays, poems and short stories while living in Cleveland.[202] The African American avant-garde poet Russell Atkins also lived in Cleveland.[204]

The American modernist poet Hart Crane was born in nearby Garrettsville, Ohio in 1899. His adolescence was divided between Cleveland and Akron before he moved to New York City in 1916. Aside from factory work during the first world war, he served as a reporter to The Plain Dealer for a short period, before achieving recognition in the Modernist literary scene. A diminutive memorial park is dedicated to Crane along the left bank of the Cuyahoga in Cleveland. In University Circle, a historical marker sits at the location of his Cleveland childhood house on E. 115 near the Euclid Avenue intersection. On the Case Western Reserve University campus, a statue of him, designed by sculptor William McVey, stands behind the Kelvin Smith Library.[205]

Cleveland was the home of Joe Shuster and Jerry Siegel, who created the comic book character Superman in 1932.[206] Both attended Glenville High School, and their early collaborations resulted in the creation of "The Man of Steel".[207] Harlan Ellison, noted author of speculative fiction, was born in Cleveland in 1934; his family subsequently moved to the nearby town of Painesville, though Ellison moved back to Cleveland in 1949. As a youngster, he published a series of short stories appearing in the Cleveland News; he also performed in a number of productions for the Cleveland Play House. D. A. Levy wrote: "Cleveland: The Rectal Eye Visions". Mystery author Richard Montanari's first three novels, Deviant Way, The Violet Hour, and Kiss of Evil are set in Cleveland. Mystery writer, Les Roberts's Milan Jacovich series is also set in Cleveland. Author and Ohio resident, James Renner set his debut novel, The Man from Primrose Lane in present-day Cleveland.

The Cleveland State University Poetry Center serves as an academic center for poetry. Cleveland continues to have a thriving literary and poetry community,[208] [209] with regular poetry readings at bookstores, coffee shops, and various other venues.[210]

Cleveland is the site of the Anisfield-Wolf Book Award, established by poet and philanthropist Edith Anisfield Wolf in 1935, which recognizes books that have made important contributions to the understanding of racism and human diversity.[211] Presented by the Cleveland Foundation, it remains the only American book prize focusing on works that address racism and diversity.[212] In an early Gay and lesbian studies anthology titled Lavender Culture,[213] a short piece by John Kelsey "The Cleveland Bar Scene in the Forties" discusses the gay and lesbian culture in Cleveland and the unique experiences of amateur female impersonators that existed alongside the New York and San Francisco LGBT subcultures.[214]

Museums and galleries [edit]

Cleveland has two main art museums. The Cleveland Museum of Art is a major American art museum, with a collection that includes more than 40,000 works of art ranging over 6,000 years, from ancient masterpieces to contemporary pieces.[215] The Museum of Contemporary Art Cleveland showcases established and emerging artists, particularly from the Cleveland area, through hosting and producing temporary exhibitions.[216] Both museums offer free admission to visitors, with the Cleveland Museum of Art declaring their museum free and open "for the benefit of all the people forever."[35] [215] [216]

Both museums are also part of Cleveland's University Circle, a 550-acre (2.2 km2) concentration of cultural, educational, and medical institutions located 5 miles (8.0 km) east of downtown. In addition to the art museums, the neighborhood also includes the Cleveland Botanical Garden, Case Western Reserve University, University Hospitals, Severance Hall, the Cleveland Museum of Natural History, and the Western Reserve Historical Society. Also located at University Circle is the Cleveland Cinematheque at the Cleveland Institute of Art, hailed by The New York Times as one of the country's best alternative movie theaters.[217]

Cleveland is home to the I. M. Pei-designed Rock and Roll Hall of Fame on the Lake Erie waterfront at North Coast Harbor downtown. Neighboring attractions include FirstEnergy Stadium, the Great Lakes Science Center, the Steamship Mather Museum, and the USSCod, a World War II submarine. Designed by architect Levi T. Scofield, the Soldiers' and Sailors' Monument at Public Square is Cleveland's major Civil War memorial and a major attraction in the city.[27] Other city attractions include the Lorenzo Carter Cabin,[15] the Grays Armory,[218] the Cleveland Police Museum,[219] and the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland's Money Museum.[220] A Cleveland holiday attraction, especially for fans of Jean Shepherd's A Christmas Story, is the Christmas Story House and Museum in Tremont.[221]

Events [edit]

The Cleveland International Film Festival has been held annually since 1977, and it drew a record 106,000 people in 2017.[222] Fashion Week Cleveland, the city's annual fashion event, is the third-largest fashion show of its kind in the United States.[223] The Cleveland National Air Show, an indirect successor to the National Air Races, has been annually held at the city's Burke Lakefront Airport since 1964.[224] Sponsored by the Great Lakes Brewing Company, the Great Lakes Burning River Fest, a two-night music and beer festival at Whiskey Island, has been held annually since 2001.[225] Proceeds from that festival benefit the Burning River Foundation, a local non-profit dedicated to "improving, maintaining and celebrating the vitality of [Cleveland's] regional freshwater resources."[226] Cleveland also hosts an annual holiday display lighting and celebration, dubbed Winterfest, which is held downtown at the city's historic hub, Public Square.[227]

Cuisine [edit]

Cleveland's mosaic of ethnic communities and their various culinary traditions have long played an important role in defining the local cuisine. Examples of these can particularly be found in neighborhoods such as Little Italy, Slavic Village, and Tremont.

Local mainstays of Cleveland's cuisine include an abundance of Polish and Central European contributions, such as kielbasa, stuffed cabbage and pierogies.[228] Cleveland also has plenty of corned beef, with nationally renowned Slyman's, on the near East Side, a perennial winner of various accolades from Esquire Magazine, including being named the best corned beef sandwich in America in 2008.[229] Other famed sandwiches include the Cleveland original, Polish Boy, a local favorite found at many BBQ and Soul food restaurants.[228] [230] With its blue-collar roots well intact, and plenty of Lake Erie perch available, the tradition of Friday night fish fries remains alive and thriving in Cleveland, particularly in church-based settings and during the season of Lent.[231]

Cleveland is noted in the world of celebrity food culture. Famous local figures include chef Michael Symon and food writer Michael Ruhlman, both of whom achieved local and national attention for their contributions to the culinary world. On November 11, 2007, Symon helped gain the spotlight when he was named "The Next Iron Chef" on the Food Network. In 2007, Ruhlman collaborated with Anthony Bourdain, to do an episode of his Anthony Bourdain: No Reservations focusing on Cleveland's restaurant scene.[232]

The national food press—including publications Gourmet, Food & Wine, Esquire and Playboy—has heaped praise on several Cleveland spots for awards including 'best new restaurant', 'best steakhouse', 'best farm-to-table programs' and 'great new neighborhood eateries'. In early 2008, the Chicago Tribune ran a feature article in its 'Travel' section proclaiming Cleveland, America's "hot new dining city".[232] In 2015, the city was named the 7th best food city in the nation by Time magazine.[233]

Breweries [edit]

Ohio produces the fifth most amount of beer in the United States, with its largest brewery being Cleveland's Great Lakes Brewing Company.[234] Cleveland has had a long history of brewing, tied to many of its ethnic immigrants, and in recent decades has reemerged as a regional leader in production.[235] In modern times, dozens of breweries exist in the city limits, including other large producers such as Market Garden Brewery and Platform Beer Company.

Breweries can be found all over the city, but the highest concentration is in the Ohio City neighborhood.[236] Cleveland is also home to expansions from other countries, including the Scottish BrewDog and German Hofbrauhaus.[237] [238]

Sports [edit]

Cleveland's current major professional sports teams include the Cleveland Guardians (Major League Baseball), Cleveland Browns (National Football League), and Cleveland Cavaliers (National Basketball Association), and the Cleveland Crunch (Major Arena Soccer League). Local sporting facilities include Progressive Field, FirstEnergy Stadium, Rocket Mortgage FieldHouse, and the Wolstein Center. The city is also host to the Cleveland Monsters of the American Hockey League, who won the 2016 Calder Cup, the first Cleveland AHL team to do so since the 1964 Barons,[239] and the Cleveland Charge of the NBA G League. Other professional teams in the city include the Cleveland Fusion of the Women's Football Alliance and Cleveland SC of the National Premier Soccer League.

The Cleveland Guardians, known as the Indians from 1915 to 2021, won the World Series in 1920 and 1948. They also won the American League pennant, making the World Series in the 1954, 1995, 1997, and 2016 seasons. Between 1995 and 2001, Progressive Field (then known as Jacobs Field) sold out 455 consecutive games, a Major League Baseball record until it was broken in 2008.[240]

Historically, the Browns have been among the most successful franchises in American football history, winning eight titles during a short period of time—1946, 1947, 1948, 1949, 1950, 1954, 1955, and 1964. The Browns have never played in a Super Bowl, getting close five times by making it to the NFL/AFC Championship Game in 1968, 1969, 1986, 1987, and 1989. Former owner Art Modell's relocation of the Browns after the 1995 season (to Baltimore creating the Ravens), caused tremendous heartbreak and resentment among local fans.[241] Cleveland mayor, Michael R. White, worked with the NFL and Commissioner Paul Tagliabue to bring back the Browns beginning in the 1999 season, retaining all team history.[242] In Cleveland's earlier football history, the Cleveland Bulldogs won the NFL Championship in 1924, and the Cleveland Rams won the NFL Championship in 1945 before relocating to Los Angeles.

The Cavaliers won the Eastern Conference in 2007, 2015, 2016, 2017 and 2018 but were defeated in the NBA Finals by the San Antonio Spurs and then by the Golden State Warriors, respectively. The Cavs won the Conference again in 2016 and won their first NBA Championship coming back from a 3–1 deficit, finally defeating the Golden State Warriors. Afterwards, an estimated 1.3 million people attended a parade held in the Cavs honor on June 22, 2016. This was the first time the city had planned for a championship parade in 50 years.[243] Basketball, the Cleveland Rosenblums dominated the original American Basketball League winning three of the first five championships (1926, 1929, 1930), and the Cleveland Pipers, owned by George Steinbrenner, won the American Basketball League championship in 1962.[244]

Jesse Owens grew up in Cleveland after moving from Alabama when he was nine. He participated in the 1936 Summer Olympics in Berlin, where he achieved international fame by winning four gold medals. A statue commemorating his achievement can be found in Downtown Cleveland at Fort Washington Park.[245] A statue of another famous Cleveland athlete, Irish American World Featherweight boxing champion Johnny Kilbane, stands in the city's Battery Park on the West Side.[246]

Cleveland State University alum and area native Stipe Miocic won the UFC World Heavyweight Championship at UFC 198 in 2016. Miocic has defended his World Heavyweight Champion title at UFC 203, the first ever UFC World Championship fight held in the city of Cleveland,[247] and again at UFC 211 and UFC 220. After losing it in 2018, Miocic regained the world title at UFC 241.

Collegiately, NCAA Division I Cleveland State Vikings have 16 varsity sports, nationally known for their Cleveland State Vikings men's basketball team. NCAA Division III Case Western Reserve Spartans have 19 varsity sports, most known for their Case Western Reserve Spartans football team. The headquarters of the Mid-American Conference (MAC) are in Cleveland. The conference also stages both its men's and women's basketball tournaments at Rocket Mortgage FieldHouse.

Several chess championships have taken place in Cleveland. The second American Chess Congress, a predecessor the current U.S. Championship, was held in 1871, and won by George Henry Mackenzie. The 1921 and 1957 U.S. Open Chess Championship also took place in the city, and were won by Edward Lasker and Bobby Fischer, respectively. The Cleveland Open is held annually.[248]

The Cleveland Marathon has been hosted annually since 1978.[249]

Environment [edit]

With its extensive cleanup of its Lake Erie shore and the Cuyahoga River, Cleveland has been recognized by national media as an environmental success story and a national leader in environmental protection.[79] Since the city's industrialization, the Cuyahoga River had become so affected by industrial pollution that it "caught fire" a total of 13 times beginning in 1868.[250] It was the river fire of June 1969 that spurred the city to action under Mayor Carl B. Stokes, and played a key role in the passage of the Clean Water Act in 1972 and the National Environmental Policy Act later that year.[72] [250] Since that time, the Cuyahoga has been extensively cleaned up through the efforts of the city and the Ohio Environmental Protection Agency (OEPA).[79] In 2019, the American Rivers conservation association named the river "River of the Year" in honor of "50 years of environmental resurgence."[68]

In addition to continued efforts to improve freshwater and air quality, Cleveland is now exploring renewable energy. The city's two main electrical utilities are FirstEnergy and Cleveland Public Power. Its climate action plan, updated in December 2018, has a 2050 target of 100 percent renewable power, along with reduction of greenhouse gases to 80 percent below the 2010 level.[251] In recent years, Cleveland has also been working to address the issue of harmful algal blooms on Lake Erie, fed primarily by agricultural runoff, which have presented new environmental challenges for the city and for northern Ohio.[252]

Government and politics [edit]

Cleveland operates on a mayor–council (strong mayor) form of government, in which the mayor is the chief executive. From 1924 to 1931, the city briefly experimented with a council–manager government under William R. Hopkins and Daniel E. Morgan before returning to the mayor–council system.[253]

The office of the mayor has been held by Frank G. Jackson since 2006. Previous mayors of Cleveland include progressive Democrat Tom L. Johnson, World War I-era War Secretary and BakerHostetler founder Newton D. Baker, U.S. Supreme Court Justice Harold Hitz Burton, two-term Ohio Governor and Senator Frank J. Lausche, former U.S. Health, Education, and Welfare Secretary Anthony J. Celebrezze, two-term Ohio Governor and Senator George V. Voinovich, former U.S. Congressman Dennis Kucinich, and Carl B. Stokes, the first African American mayor of a major U.S. city.[71]

Another nationally prominent Ohio politician, former U.S. President James A. Garfield, was born in Cuyahoga County's Orange Township (today the Cleveland suburb of Moreland Hills).[254] His resting place is the James A. Garfield Memorial in Cleveland's Lake View Cemetery.[255]

From the Civil War era to the 1940s, Cleveland was primarily dominated by the Republican Party, with the notable exceptions of the Johnson and Baker mayoral administrations.[253] Businessman and Senator Mark Hanna was among Cleveland's most influential Republican figures, both locally and nationally.[256] In addition to the established support of organized labor, the Cuyahoga County Democratic Party, led by former mayor Ray T. Miller, was able to secure the support of the city's ethnic European and African American communities in the 1940s.[253] Beginning with the Lausche administration, Cleveland's political orientation shifted to the Democratic Party and, with the exceptions of the Perk and Voinovich administrations, it has remained dominated by the Democrats ever since.[253]

Today, while other parts of Ohio, particularly Cincinnati and the southern portion of the state, support the Republicans, Cleveland commonly produces the strongest support in the state for the Democrats.[257] At the local level, elections are nonpartisan. However, Democrats still dominate every level of government. During the 2004 Presidential election, although George W. Bush carried Ohio by 2.1%, John Kerry carried Cuyahoga County 66.6%–32.9%, his largest margin in any Ohio county.[258] The city of Cleveland supported Kerry over Bush by the even larger margin of 83.3%–15.8%.[259] As a result of the 2010 Census, Ohio lost two Congressional seats, which affected Cleveland's districts in the northeast part of the state.[260] Today, Cleveland is split between two congressional districts. Most of the western part of the city is in the 9th District, represented by Marcy Kaptur. Most of the eastern part of the city, as well as most of downtown, is in the 11th District, represented by Marcia Fudge. Both are Democrats, two of four representing Ohio.

Cleveland hosted three Republican national conventions in its history, in 1924, 1936, and 2016.[261] The city also hosted the Radical Republican convention of 1864.[262] Cleveland has not hosted a national convention for the Democrats, despite the position of Cuyahoga County as a Democratic stronghold in Ohio.

Cleveland has hosted several national election debates, including the second 1980 U.S. Presidential debate, the 2004 U.S. Vice-Presidential debate, one 2008 Democratic primary debate, and the first 2020 U.S. Presidential debate.[263] Founded in 1912, the City Club of Cleveland provides a platform for national and local debates and discussions. Known as Cleveland's "Citadel of Free Speech," it is one of the oldest continuous independent free speech and debate forums in the country.[264] [265]

Public safety [edit]

Police and law enforcement [edit]

Like in other major American cities, crime in Cleveland is concentrated in areas with higher rates of poverty and lower access to jobs.[266] [267] In recent years, the rate of crime in the city has seen a significant decline, following a nationwide trend in falling crime rates.[266] Cleveland Police statistics published in 2019 showed that rates for violent crimes and property crimes in Cleveland dropped substantially in 2018. The rate of property crimes specifically fell by 30% since 2016.[268]

Cleveland's law enforcement agency is the Cleveland Division of Police, established in 1866.[269] [270] The division has 1,444 sworn officers as of 2016.[271] Cleveland has five police districts.[272] The district system was introduced in the 1930s by Cleveland Public Safety Director Eliot Ness (of the Untouchables), who later ran for mayor of Cleveland in 1947.[269] [273] The division has been recognized for several "firsts," including the "first criminal conviction secured by matching a palm print lifted from a crime scene to a suspect."[270] The current Chief of Police is Calvin D. Williams.[274]

In December 2014, the United States Department of Justice announced the findings of a two-year investigation, prompted by a request from Mayor Frank Jackson, to determine whether the Cleveland Police engaged in a pattern of excessive force.[275] [276] As a result of the Justice Department report, the city agreed to a consent decree to revise its policies and implement new independent oversight over the police force.[277] The consent decree, released on May 26, 2015, mandated sweeping changes to the Cleveland Police.[278] [279] On June 12, 2015, Chief U.S. District Judge Solomon Oliver Jr. approved and signed the consent decree, beginning the process of police reform.[280]

Fire department [edit]

Cleveland is served by the firefighters of the Cleveland Division of Fire, established in 1863.[281] The fire department operates out of 22 active fire stations throughout the city in five battalions. Each Battalion is commanded by a Battalion Chief, who reports to an on-duty Assistant Chief.[282] [283]

The Division of Fire operates a fire apparatus fleet of twenty-two engine companies, eight ladder companies, three tower companies, two task force rescue squad companies, hazardous materials ("haz-mat") unit, and numerous other special, support, and reserve units. The current Chief of Department is Angelo Calvillo.[284]

Emergency Medical Services [edit]

Cleveland EMS is operated by the city as its own municipal third-service EMS division. Cleveland EMS is the primary provider of Advanced Life Support and ambulance transport within the city of Cleveland, while Cleveland Fire assists by providing fire response medical care.[285] Although a merger between the fire and EMS departments was proposed in the past, the idea was subsequently abandoned.[286]

Media [edit]

Print [edit]

Cleveland's primary daily newspaper is The Plain Dealer and its associated online publication, Cleveland.com.[287] Defunct major newspapers include the Cleveland Press, an afternoon publication which printed its last edition on June 17, 1982;[288] and the Cleveland News, which ceased publication in 1960.[289] Additional publications include: the Cleveland Magazine, a regional culture magazine published monthly;[290] Crain's Cleveland Business, a weekly business newspaper;[291] and Cleveland Scene, a free alternative weekly paper which absorbed its competitor, the Cleveland Free Times, in 2008.[292] Nationally distributed rock magazine Alternative Press was founded in Cleveland in 1985, and the publication's headquarters remain in the city.[293] [294] [295] The digital Belt Magazine was founded in Cleveland in 2013.[296] Time magazine was published in Cleveland for a brief period from 1925 to 1927.[297]

Cleveland's ethnic publications include: the Call and Post, a weekly newspaper that primarily serves the city's African American community;[298] the Cleveland Jewish News, a weekly Jewish newspaper;[299] the bi-weekly Russian language Cleveland Russian Magazine for the Russian and post-Soviet community;[300] the Mandarin Erie Chinese Journal for the city's Chinese community;[301] La Gazzetta Italiana in English and Italian for the Italian community;[302] the Ohio Irish American News for the Irish community;[303] and the Spanish language Vocero Latino News for the Latino community.[304] Historically, the Hungarian language newspaper Szabadság served the Hungarian community.[305]

Television [edit]

Moon over Downtown Cleveland

Cleveland is the 19th-largest television market by Nielsen Media Research (as of 2013[update]–14).[306] The market is served by 10 full power stations, including: WEWS-TV (ABC), WJW (Fox), WKYC (NBC), WOIO (CBS), WVIZ (PBS), WUAB (The CW), WVPX-TV (Ion), WQHS-DT (Univision), WDLI-TV (Court TV), and the independent WBNX-TV.[307]

The Mike Douglas Show, a nationally syndicated daytime talk show, began in Cleveland in 1961 on KYW-TV (now WKYC), while The Morning Exchange on WEWS-TV served as the model for Good Morning America.[308] [309] Tim Conway and Ernie Anderson first established themselves in Cleveland while working together at KYW-TV and later WJW-TV (now WJW). Anderson both created and performed as the immensely popular Cleveland horror host Ghoulardi on WJW-TV's Shock Theater, and was later succeeded by the long-running late night duo Big Chuck and Lil' John.[310]

Radio [edit]